The United States hit an electric vehicle milestone late last year. In October 2018, we crossed the threshold of one million plug-in electric vehicles sold. Electric vehicle sales are forecasted to expand even faster as new models become available to consumers. You would think that this means only positive environmental and economic outcomes.

However, if electric vehicle adoption and subsequent charging isn’t managed well, the ability of the electric system to handle this new load may reduce the overall value of this transition from gas to electric vehicles. In addition to negatively impacting electric system reliability, unmanaged electric vehicle charging may impede the adoption of electric vehicles, increase electric system costs, and increase carbon emission through the increased use of gas-fired peaking plants.

Some electric utilities are getting ahead of this issue by promoting programs to shift the timing of residential charging and promote workplace charging. With these changes, electric vehicles can be beneficial to the electric grid. This paper, featured by GreenBiz, highlights some recent actions by electric utilities to support electric vehicle workplace charging.

Electric Vehicle Growth Can Challenge Grid Operations

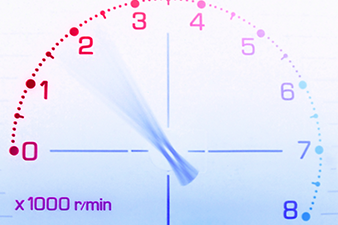

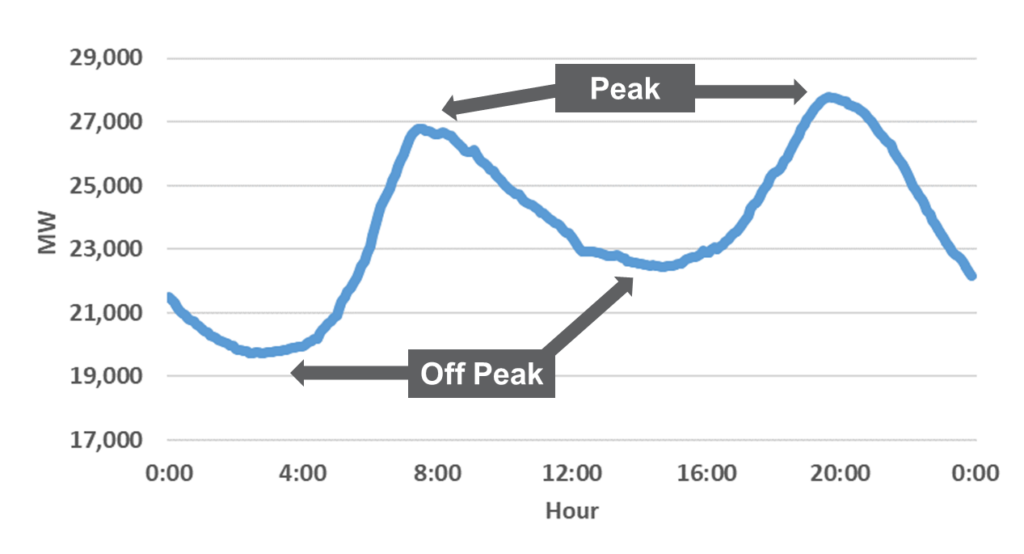

Growth in electric vehicles is positive in many ways but will also increase demand on the electric grid. This can be overall positive or negative, depending upon when these electric vehicles charge. If charging occurs at off-peak times, the system can handle it with little impact, and electricity sales can provide great incremental value. System demand typically peaks during the evening hours (see Figure 1). If charging occurs in the evenings, it could cause stress on the system and require additional infrastructure to support the increased demand.

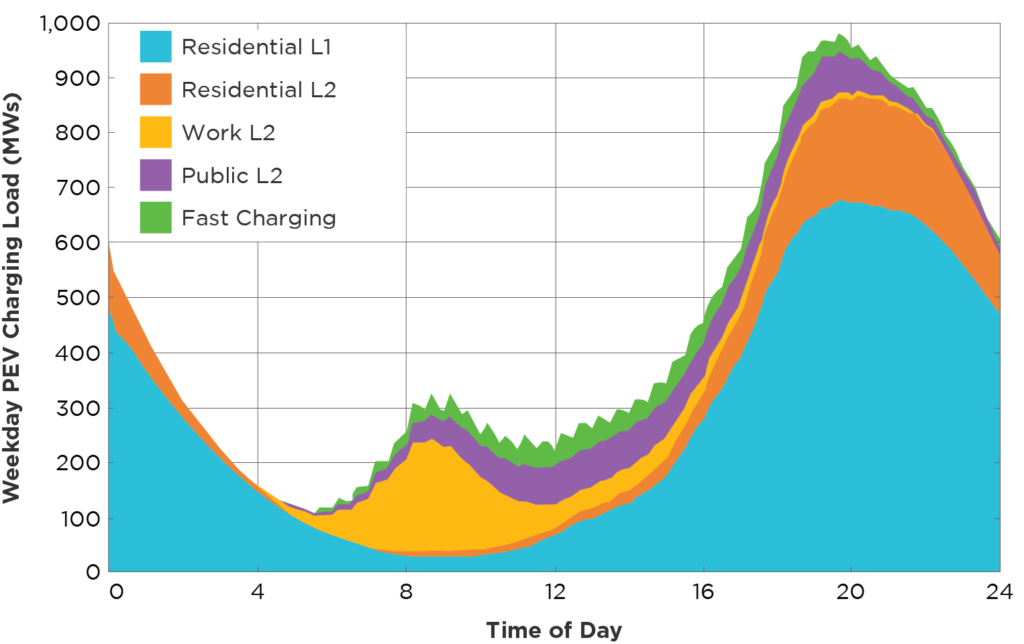

Unfortunately, recent studies show that, absent a change in behavior, charging is forecasted to exacerbate peak load. A study by the California Energy Commission and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory is one of the first reports to show that the overwhelming majority of electric vehicle charging is forecasted to occur at home (blue and red in Figure 2) during evening peak hours.

| Figure 1. CAISO Electric Demand(March 12, 2019)[1] | Figure 2. Weekday California Electric Vehicle Charging Load Profile in 2025[2] |

|

|

There are two strategies being employed for shifting this charging profile to more off-peak:

- Offering managed charging, which includes demand response and time-of-use rates, to shift home-charging times overnight

- Promotion of workplace charging to encourage more “middle-of-the-day” charging

We find many instances in which utilities are exploring managed charging; however, workplace charging infrastructure is severely lacking. A 2019 study by The International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) found that half of the largest U.S. metropolitan areas have less than 16 percent of the estimated workplace infrastructure that will be needed by 2025.[3]

To address this gap, some electric utilities are becoming active in incentivizing the installation of workplace charging infrastructure. The following summarizes some of the key advances in workplace charging.

Electric Utilities Increasingly Providing Workplace Charging Incentives

To understand how electric utilities are approaching this segment of the electric vehicle market, we examined workplace charging proposals from the 20 largest electric utilities in the United States.[4]

In broad terms, we found utility workplace charging focused on Level 2 chargers, as these chargers are widely seen as the proper charging equipment for workplace environments. Electric vehicles will be charging for an extended period of time at workplaces, so direct-current fast-charging equipment can be an unnecessary investment.

While there may be alignment on the type of workplace chargers, there is notable diversity in workplace charging infrastructure incentives (see Figure 3).

One approach being pursued by utilities is to provide make-ready infrastructure for workplace chargers. This means installing the necessary infrastructure to the point where the electric vehicle charger can be installed.

A second approach, which can be coupled with make-ready infrastructure, is for the electric utility to provide workplace hosts with rebates or grants for charging equipment. The rebates or grants provide capital to site hosts to purchase and install charging equipment.

The third approach extends utility ownership all the way to the electric charger. In this instance, the utility owns and operates the infrastructure at the host site. This approach is less common but is becoming more popular along with rebates and grants.

Figure 3. Workplace Charging Infrastructure Incentives

| Category | Description | Select Utilities |

| Utility Funds Make-Ready Infrastructure | Utility provides all electric infrastructure up to the utility meter and also the electrical panel, conduits, and wires up to the charger | DTE Energy, Consumers Energy, AEP Ohio |

| Charger Rebate/Grant | Utility provides rebates/grants toward the cost of charging equipment | Georgia Power, PSE&G, PECO |

| Utility Owns Charger | Utility purchases, installs, and owns all charging infrastructure | PacifiCorp, Duke Energy Florida |

Workplace charging infrastructure incentives address the initial costs required to set up workplace charging. Once installed, workplaces may see higher electric bills following the installation of vehicle chargers. The additional expense comes from increased electricity consumption, as well as changes in demand charges, which are based on an electric customer’s peak demand.

To address these billing challenges, electric utilities are encouraging the growth of workplace charging with rate designs that are electric vehicle specific (see Figure 4).

One billing structure used by utilities is an electric vehicle-specific tariff or rate. These rates, typically time-of-use rates, incentivize electric vehicle charging during non-peak hours. These tariffs can be especially useful in regions with high penetration of solar capacity.

Consider PG&E, one of the investor-owned utilities in California. The utility has proposed a commercial electric vehicle rate with a “super off-peak” period from 9:00 AM to 2:00 PM. Workplace charging creates demand when the electric system is coping with oversupply risks driven by solar generation.

Utilities are also exploring programs which reduce or temporarily remove demand charges related to electric vehicle charging. By reducing demand charges for demand-billed customers, utilities offset a portion of the demand charge that could be incurred as a result of electric vehicle charging.

A novel approach to electric vehicle charging is the creation of a subscription service, which would charge hosts a subscription fee per month. Compared to electric vehicle-specific tariffs or demand charge reductions, this is a new approach to workplace charging.

Figure 4. Workplace Charging Billing Designs

| Category | Description | Select Utilities |

| Electric Vehicle-Specific Tariffs | Utility modifies tariff to better suit electric vehicle charging | PG&E, ConEd |

| Demand Charge Rebate | Utility provides a bill credit to offset a portion of an increased demand charge due to workplace charging | Southern California Edison |

| Electric Vehicle Charging Subscription Plan | Customers would pay a subscription fee per month corresponding to level of electric vehicle charging load | PG&E |

Workplace Charging Benefits Extend beyond the Grid

Employers may consider workplace charging as a unique employee benefit. Workplaces are an ideal charging location, as they are the second most frequent parking location behind homes.[5] Consequently, the addition of workplace charging may be an attractive feature to current and potential employees driving or considering electric vehicles.

Employees also benefit from the installation of workplace charging infrastructure. Workplace charges can be the primary chargers for drivers without dedicated charging at home. Additionally, workplace chargers can provide flexibility and relieve range anxiety for other electric vehicle drivers.

Workplace charging also allows employers to advance sustainability goals, such as emission reductions, by reducing Scope 3 emissions. Studies have shown that workplace charging results in more electric miles for plug-in electric vehicles[6] and that total transportation emissions decrease when electric vehicle owners have access to workplace charging.[7]

The expansion of workplace charging has also been shown to increase electric vehicle ownership. In fact, the availability of workplace charging is the third most significant driver of electric vehicle adoption behind vehicle model availability and public direct-current fast charging.[8] With the transportation sector the leading source of carbon dioxide emissions, a key sustainability goal could be encouraging and supporting drivers to transition from gas to electric.

Summary

Electric transportation is an emerging technology poised for rapid adoption in the United States. If current electric vehicle charging behavior is not changed, electric vehicles will stress the system at the wrong time and require additional infrastructure to meet peak demand. As this growth challenges the electric grid, workplace charging can be a key component in a comprehensive approach to optimizing the cost of infrastructure needed to support electric vehicles. During this transition, electric utilities and workplace charging hosts can contribute to the long-term success of electric vehicles.

Additional Contributing Author: Chris Vlahoplus

[1] CAISO

[2] California Energy Commission and NREL

[3] ICCT. “Quantifying the Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure Gap Across U.S. Markets,” p.20

[4] Electric end-use customers (from S&P Global Market Intelligence)

[5] ICCT. “Quantifying the Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure Gap Across U.S. Markets,” p.10

[6] Electricity Journal. “CO2 emissions associated with electric vehicle charging: the impact of electricity generation mix, charging infrastructure availability and vehicle type,” p.82

[7] ibid

[8] ICCT. “The Continued Transition to Electric Vehicles in U.S. Cities,” p.36